22. AGX Vehicle

The AGX Vehicle module provides various functionality for simulating vehicles and machines.

22.1. Tracks

A tracked vehicle is an object containing one or more tracks. Each track contains two or more wheels and an arbitrary number of treads.

AGX Dynamics provides two models for simulating tracked vehicles, each suited for different use cases.

Full-Degree Tracks Model – detailed per-node rigid body simulation, high realism but computationally heavy.

Low-Degree Tracks Model – simplified, wheel-based model, faster and more stable.

The Track class has two constructors, and the choice of constructor determines which track model is active. The recommended constructor is the one that takes a reference rigid body (typically the vehicle chassis when simulating vehicles). Using this constructor will initialize the Low-Degree Tracks Model by default. If desired, this model can be switched to the Full-Degree Tracks Model by explicitly enabling it with setEnableFullDegreeModel(true).

If instead you use the constructor without a reference rigid body, then only the Full-DoF Model is supported, and that will be the model used during simulation.

agx::RigidBodyRef referenceRigidBody = new agx::RigidBody();

agxVehicle::TrackRef track = new agxVehicle::Track(referenceRigidBody,

numNodes,

width,

thickness);

This sections below describes how to create and configure tracks, add wheels and route them, set initial tension and node geometry, tune friction and material parameters, merge nodes for performance, and adjust track properties such as track stiffness, damping, and hinge range.

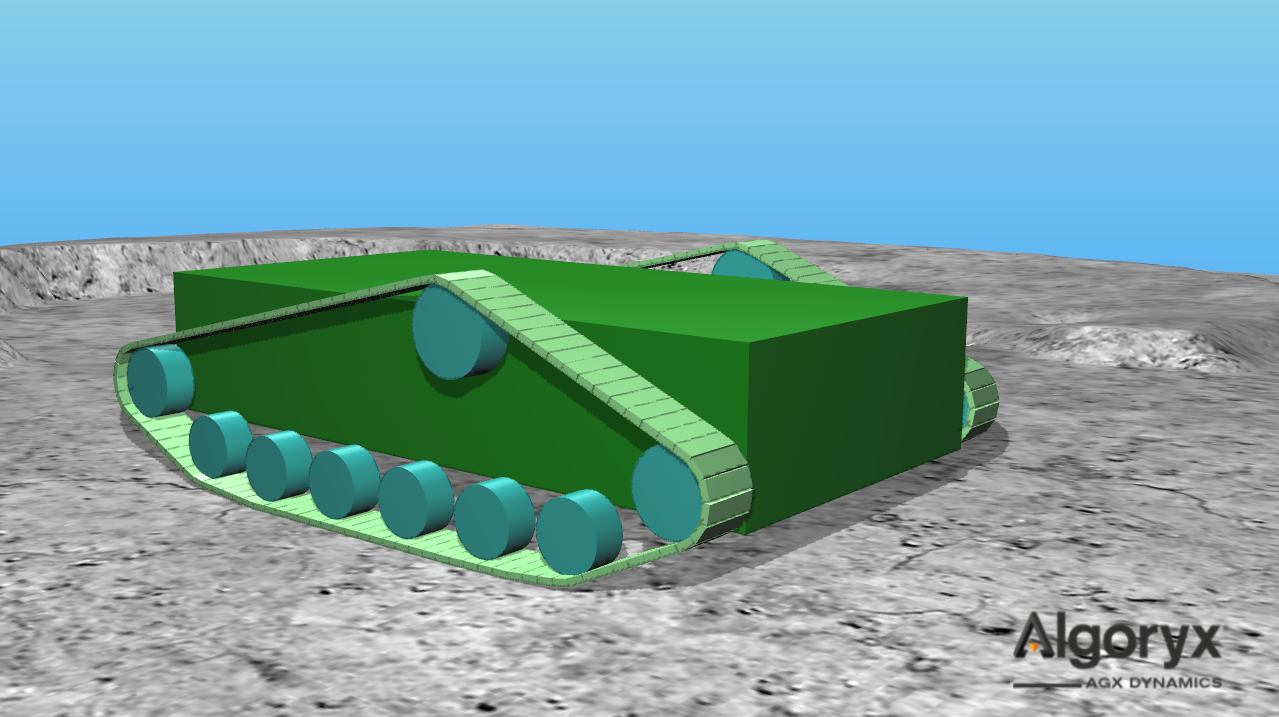

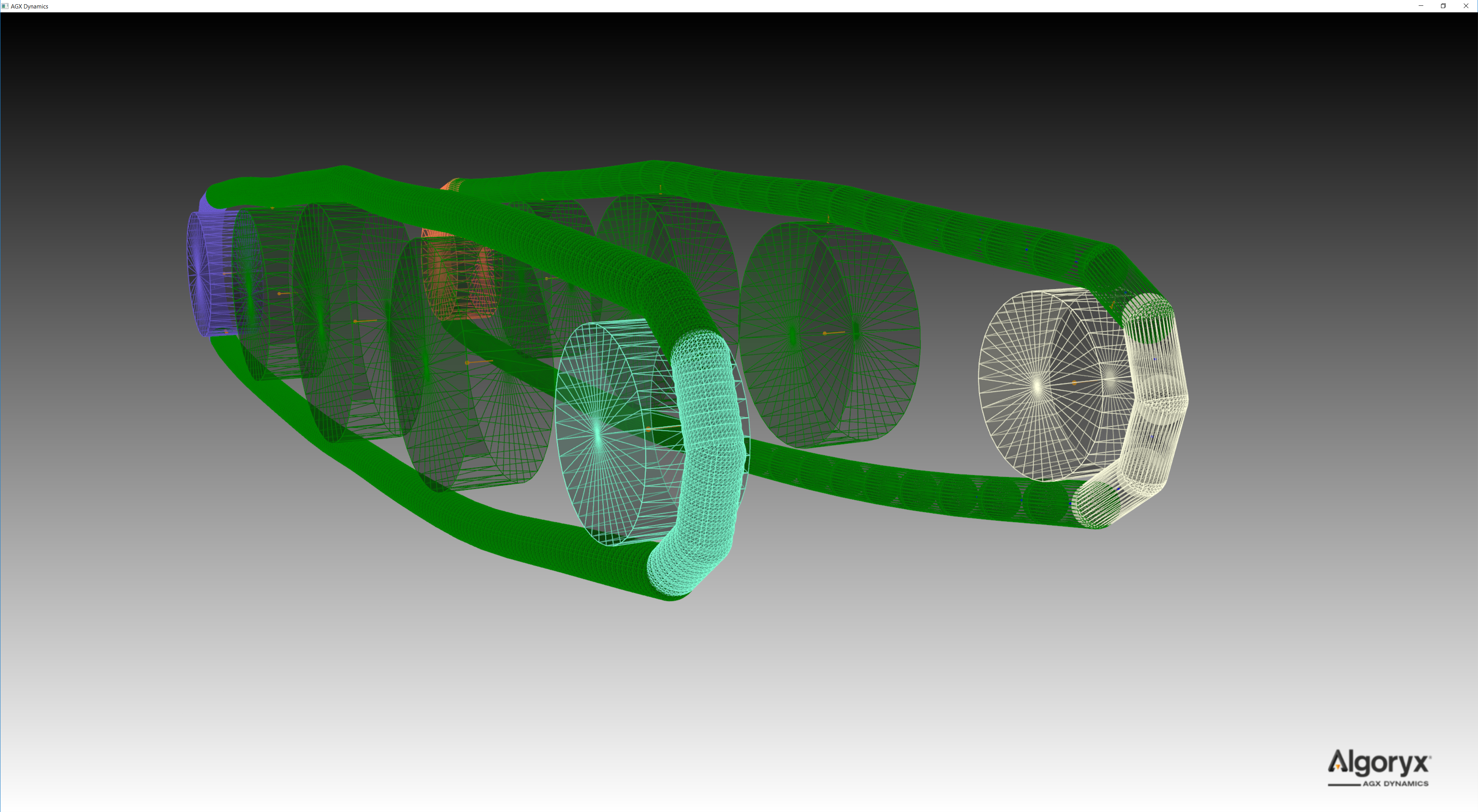

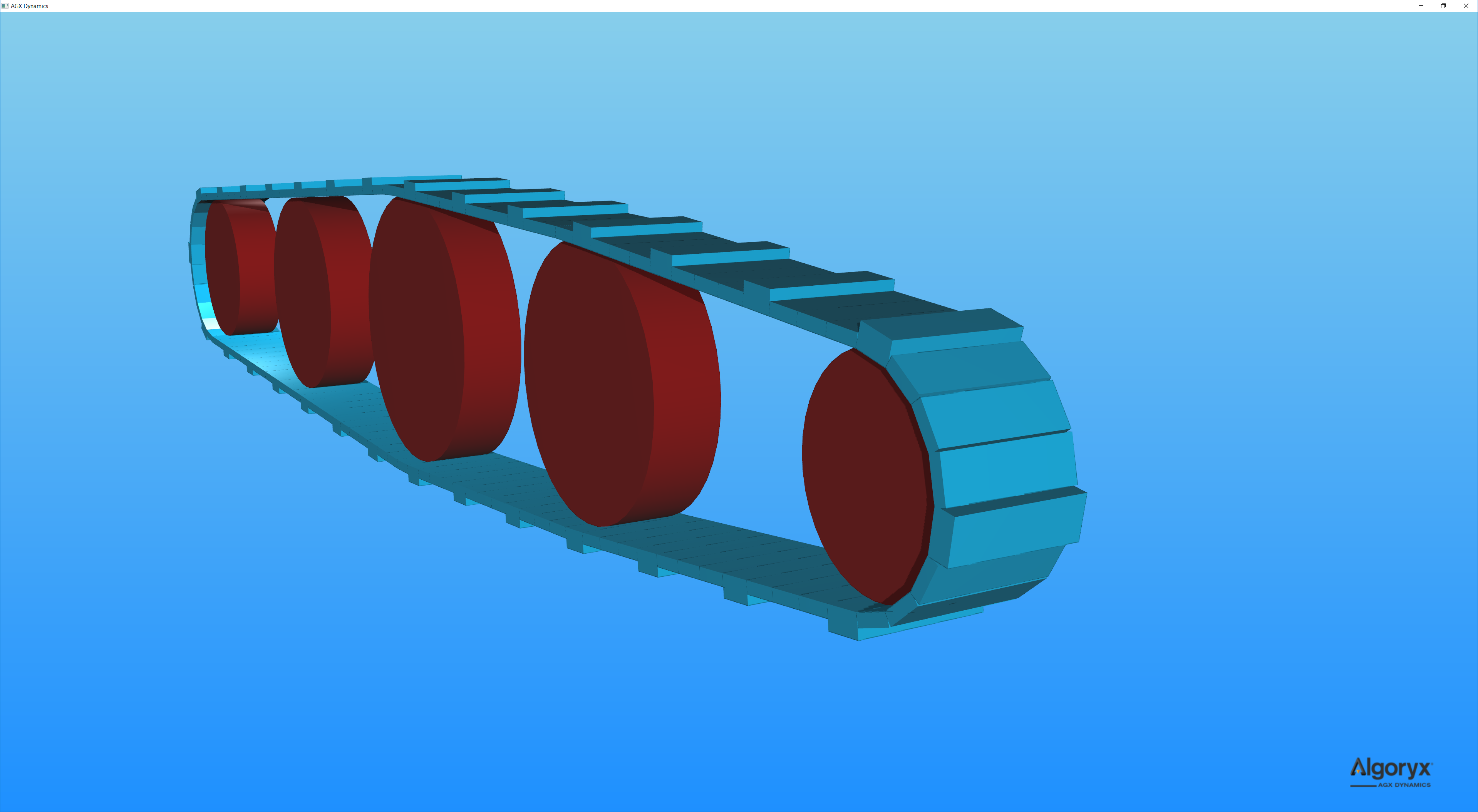

Fig. 22.1 Tracked vehicle with two tracks, each track has nine wheels and 100 treads.

22.1.1. Full-Degree Tracks Model

The Full-Degree Tracks Model (agxVehicle::Track) is based on a lumped-element approach with multiple

degrees of freedom. Each track shoe is represented by a rigid body connected through rotational joints,

accurately capturing the physical constraints between components and their interaction with terrain and other bodies.

This model delivers high physical realism and is well suited for applications where detailed track behavior is important.

However, its complexity can make setup challenging, especially for fast-moving vehicles. High track speeds require small simulation time steps to maintain constraint accuracy, which can lead to numerical instabilities in demanding scenarios.

22.1.2. Low-Degree Tracks Model

The Low-Degree Tracks Model is optimized for high-speed vehicle simulations and uses a reduced number of degrees of freedom. In this model, the track nodes and hinge joints are replaced by a smaller set of bodies and constraints, with degrees of freedom proportional to the number of wheels rather than the number of track nodes.

Between each wheel pair, a sensor box body is added and prismatic-constrained to the chassis. Track tension is modeled using massless wire constraints: a global tension element wraps around all wheels, and local tension constraints connect each pair of track-contacting wheels. Track-ground interaction is approximated using the wheels and sensor boxes, which together define the track topology and tension forces.

This approach improves numerical stability and performance for high-speed simulations while retaining the essential dynamics of tracked vehicles.

22.1.2.1. agxVehicle::TrackImplementation

The default model depends on what constructor you use when you create your tracks model but it is recommended to use the constructor described below with a given reference rigid body, this will initiate the Low-Degree Tracks Model (vs the Full-Degree Tracks Model).

Creating Tracks

agx::RigidBodyRef referenceRigidBody = new agx::RigidBody();

agxVehicle::TrackRef track = new agxVehicle::Track(referenceRigidBody,

numNodes,

width,

thickness);

Switching Between Models

You can switch between the Full-Degree Tracks Model and the Low-Degree Tracks Model at runtime:

// Enable or disable the full degrees-of-freedom model

track->setEnableFullDegreeModel(true); // Activates full DOF

track->setEnableFullDegreeModel(false); // Activates low DOF (default)

bool isFullDofActive = track->getEnableFullDegreeModel();

Using Custom Track Implementations

You can also explicitly assign a custom track implementation. In the example below we use the default Low-Degree Tracks Model:

// Assign a runtime implementation

agxVehicle::TrackImplementation* customImpl =

new agxVehicle::LowDofTrackImplementation(referenceRigidBody);

track->setTrackImplementation(customImpl, true);

This allows fine-grained control over how the track is simulated, making it possible to use a custom implementation or switch between implementations dynamically.

22.1.2.2. agxVehicle::LowDofTrackImplementation

The LowDofTrackImplementation is the default implementation when setEnableFullDegreeModel(false) is used.

In this model:

Track node bodies and hinge DOFs are removed and the track nodes are approximated with boxes between the wheels.

The number of DOFs is proportional to the number of wheels rather than the number of nodes.

Track nodes are animated based on wheel geometries and rotation speeds, enabling realistic visual rendering.

22.1.3. agxVehicle::Wheel

Base class of an abstraction of a wheel of arbitrary geometry. An agxVehicle::Wheel is constructed

given radius, rigid body and a relative frame.

- Definition:

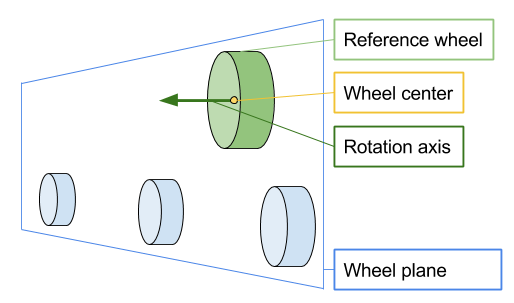

A wheel has a center, a radius and a rotation axis.

Since the given rigid body can be any user defined object, the relative frame defines the center and rotation axis of the wheel and is given in the frame of the wheel body.

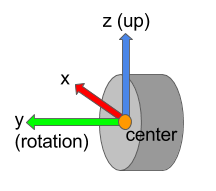

The resulting frame should have the rotation axis about y and up axis along z.

Fig. 22.2 Cylindrical wheel with wheel frame defining center position, rotation and up axes.

22.1.4. agxVehicle::TrackWheel

An agxVehicle::TrackWheel is an agxVehicle::Wheel and inherits the definitions of center,

radius and reference frame. The track wheel comes with a few more important features; model and property.

This means that each track wheel is of a certain model and contains a set of properties.

Model |

Description |

|---|---|

Sprocket |

Driving wheel - this wheel’s shaft is connected to the powerline/motor. Sprockets are normally geared where the treads wont slip while in good touch with the surface of the sprocket. |

Idler |

Geared, non-powered wheel. Similar surface properties as the sprocket but this model isn’t powered. |

Roller |

Intermediate track-return or road wheel. |

The properties associated to the track wheels are by default assigned given the model.

Property |

Description |

Model |

|---|---|---|

Merge nodes |

Treads/nodes are merged to the wheel when in contact, mimicking geared interaction (or infinite friction). |

Sprockets and idlers |

Split segments |

Splits merged segments of treads/nodes when in contact with wheels with this property. |

Optional |

Move nodes to rotation plane |

If enabled - when a node is merged to the wheel, move the node into the plane defined by the wheel center position and rotation axis. This will prevent the tracks from sliding of its path but all wheels with MERGE_NODES must be aligned. |

Optional |

Move nodes to wheel |

Similar to move nodes to rotation plane but with this property enabled the node will also be placed on the surface of the wheel. |

Optional |

Example of a cylindrical track wheel, trivially created with reference frame oriented with the rigid body. The wheel is attached in world with a hinge about the rotation axis and zero rotation axis offset:

const auto wheelRadius = 0.45;

const auto wheelHeight = 0.35;

agx::RigidBodyRef wheelRb = new agx::RigidBody( "wheelRb" );

wheelRb->add( new agxCollide::Geometry( new agxCollide::Cylinder( wheelRadius, wheelHeight ) ) );

agxVehicle::TrackWheelRef wheel = new agxVehicle::TrackWheel( agxVehicle::TrackWheel::SPROCKET,

wheelRadius,

wheelRb );

// Attaching the wheel with a hinge named "hinge" in world (nullptr) and

// 0.0 meters offset along the rotation axis.

auto hinge = wheel->attachHinge( "hinge", nullptr, 0.0 );

hinge->getMotor1D()->setEnable( true );

hinge->getMotor1D()->setSpeed( 1.0 );

simulation->add( wheelRb );

simulation->add( hinge );

It’s hard to create an example with a more complex setup with non-identity reference frame. To verify the

wheel frame, from case to case, render the frame using wheel->getTransform(), for example:

#include <agxRender/RenderSingleton.h>

...

agxRender::debugRenderFrame( wheel->getTransform(), 0.25, agxRender::Color::Red() );

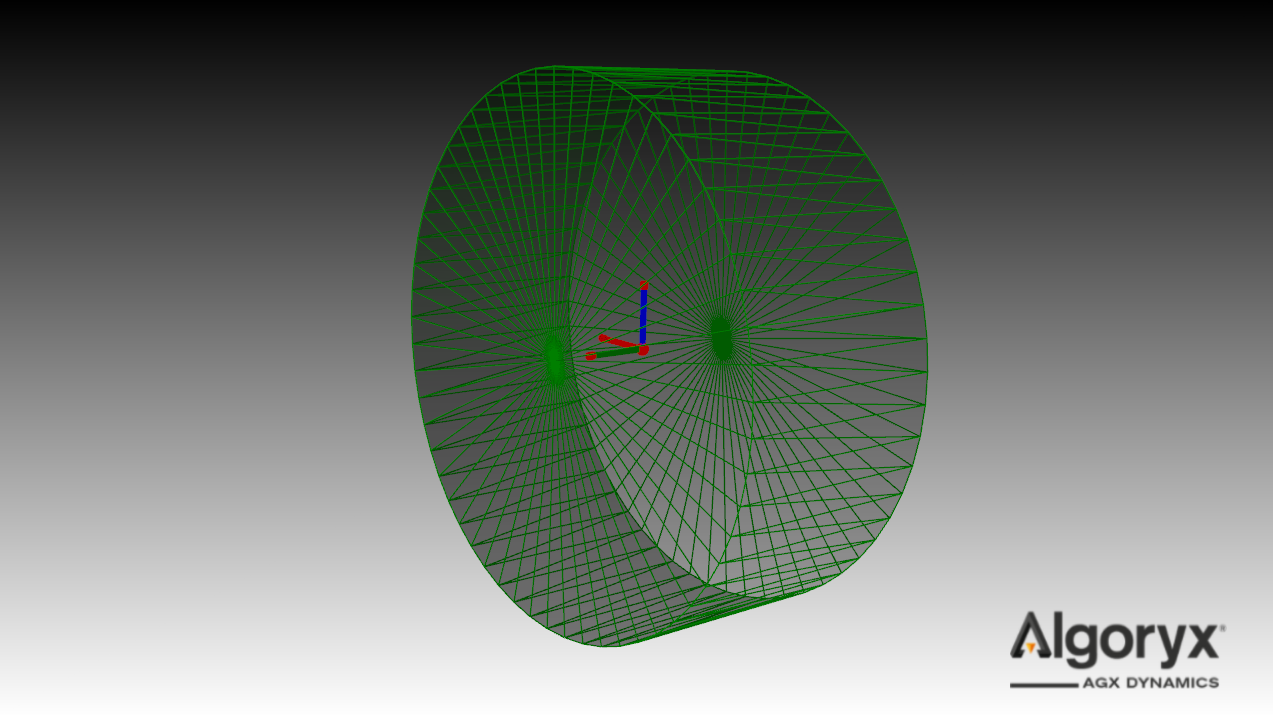

Fig. 22.3 Track wheel with radius 0.45 m and height 0.35 m. Hinged in world with hinge axis along the green (wheel) rotation axis.

22.1.5. agxVehicle::Track

Assembly object representing a continuous track with a given number of treads/nodes.

22.1.5.1. Initialization

An agxVehicle::Track is instantiated given the referenceRigidBody desired number of nodes, width, thickness of each node and initialTension. The width and thickness are both reference values - i.e., not actual, meaning the geometry may have different dimensions. The thickness value is used place the nodes as close as possible to the surface of the wheels.

The initialTension defines the tension in the track after it is initiated. This gives an amount by which each node is shortened to generate tension in the track and wheel system. Ideally, the track tension equals the shortening distance multiplied by the track tensile stiffness. Because contacts and other dynamic effects are present, the exact tension after initialization cannot be predicted. A scale factor of four is applied to approximately compensate for frictional effects, and the initial node distance is determined from this scale factor, the specified tension, and the tensile stiffness of the track.

The referenceRigidBody is the reference body that this track is attached to, normally the chassis of a vehicle. Note that the track is routed around track wheels that are connected directly or via links to this rigid body.

The ‘’unknown’’ parameter is the length of each node. The length of the nodes is calculated during initialization to properly fit the track round the wheels.

22.1.5.1.1. Routing with wheels

Routing of the tracks is made by adding wheels to the track. Given number of nodes in the track, thickness of the nodes and wheel configuration (transform and radius), the track routing algorithm will calculate the length each node should have for the track to go outside all wheels.

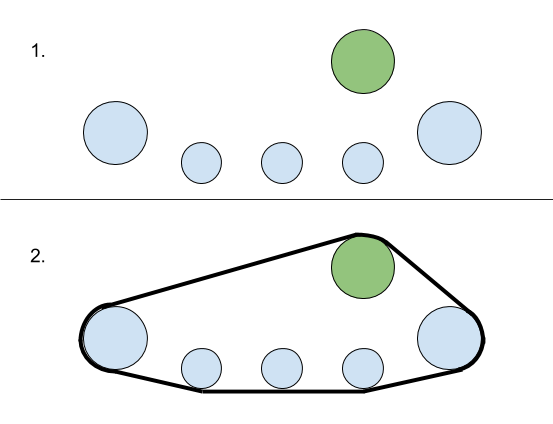

Fig. 22.4 Initial wheel configuration (1) and resulting track route (2).

Note

It doesn’t matter in which order the wheels has been added to the tracks.

Note

It’s currently only possible to initialize the tracks in a convex shape.

Small example given an array of wheel bodies that has been positioned and an array of wheel radii. The first wheel will be set to be the sprocket, all others are rollers:

// Use your chassis as the rigid body, or nullptr if the track is attached to the world

agx::RigidBodyRef referenceRigidBody = new agx::RigidBody();

agxVehicle::TrackRef track = new agxVehicle::Track( referenceRigidBody,

numNodes,

width,

thickness,

InitialTrackTension { 2e4 } );

for ( agx::UInt i = 0; i < wheelBodies.size(); ++i ) {

agxVehicle::TrackWheelRef wheel = new agxVehicle::TrackWheel( i == 0 ?

agxVehicle::TrackWheel::SPROCKET :

agxVehicle::TrackWheel::ROLLER,

wheelRadius[ i ],

wheelBodies[ i ] );

track->add( wheel );

}

// The track will be initialized when added to a simulation if

// agxVehicle::Track::initialize hasn't been called explicitly.

simulation->add( track );

22.1.5.1.2. Reference wheel

The reference wheel is used as reference during initialization of the tracks. The nodes will be positioned in the plane defined by the reference wheel position and rotation axis.

Fig. 22.5 Plane defined by the reference wheel center position and rotation axis.

The reference wheel is defined to be the first sprocket wheel (if any), otherwise first idler wheel (if any), otherwise the first roller.

- Definition:

The reference wheel is the first sprocket wheel added to a track.

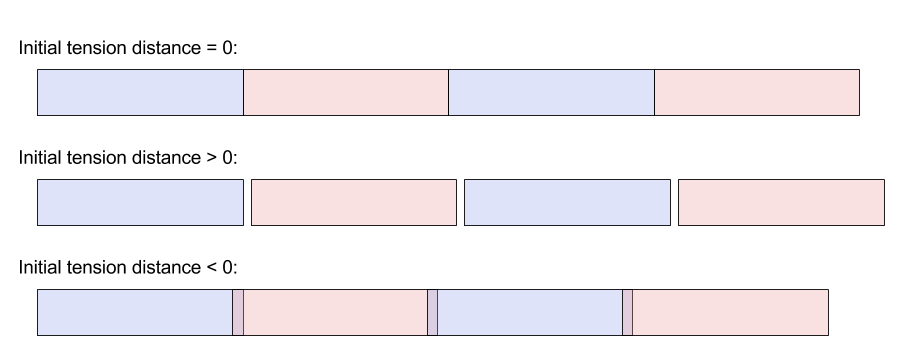

22.1.5.1.3. Initial tension

If the track finds a solution to the initial configuration and the actual geometry of the nodes matches the input thickness - the tension on the tracks will be close to zero. If the vehicle/object doesn’t have e.g., a tensioner, it’s possible to initialize the tracks with tension.

The initial tension parameter can be specified as either a distance or a force. Using a force value is less precise, as it is difficult to establish an initial state where the resulting tension exactly matches the specified force without simulating the system to equilibrium. When a force is provided, the initial node distance is approximated from the given tension and the tensile stiffness of the track, scaled by a factor of four.

A positive initial node distance shortens the spacing between nodes during initialization, increasing tension. A negative value increases the spacing between nodes, reducing or eliminating tension.

Fig. 22.6 Initial tension distance when zero (no tension), positive (initially stretched) and negative (initially compressed).

22.1.5.1.4. Node geometry

As for the wheels, the geometry of the nodes are completely arbitrary. Box is used by default.

Create geometry callbacks are fired when the node has been positioned. The z-axis of the node body is pointing in the direction of the track and the model center must be at the begin position of the node. The default ‘createGeometryBox’’ function looks like this:

void createGeometryBox( const TrackNode& node )

{

// Node half extents = (0.5 * thickness, 0.5 * width, 0.5 * length)

agxCollide::BoxRef box = new agxCollide::Box( node.getHalfExtents() );

agxCollide::GeometryRef geometry = new agxCollide::Geometry( box );

// Model center is begin of node, translate geometry forward 0.5 * length (along z).

const auto transform = agx::AffineMatrix4x4::translate( 0,

0,

node.getHalfExtents().z() );

geometry->setLocalTransform( transform );

node.getRigidBody()->add( geometry );

}

Adding the track to the simulation without calling initialize beforehand is equivalent to call initialize given ‘’createGeometryBox’’ and then adding the track to the simulation:

// Default initialization...

simulation->add( track );

// ...is equivalent to:

anotherTrack->initialize( agxVehicle::utils::createGeometryBox );

simulation->add( anotherTrack );

Example of two tracks where one is initialized with several sphere shapes as geometry (initialize function) and the other with capsules (interface):

class NodeCapsuleInitializer : public agxVehicle::TrackNodeOnInitializeCallback

{

public:

NodeCapsuleInitializer() {}

virtual void onInitialize( const agxVehicle::TrackNode& node ) override

{

agxCollide::CapsuleRef capsule = new agxCollide::Capsule( 0.5 * node.getWidth(),

node.getLength() );

node.getRigidBody()->add( new agxCollide::Geometry( capsule ),

agx::AffineMatrix4x4::rotate( agx::Vec3::Y_AXIS(),

agx::Vec3::Z_AXIS() ) *

agx::AffineMatrix4x4::translate( 0, 0, 0.5 * node.getLength() ) );

}

protected:

virtual ~NodeCapsuleInitializer() {}

};

const agx::Real sphereRadius = 0.1;

// Creates track with five wheels, 60 nodes and width = thickness = 2.0 * sphereRadius.

agxVehicle::TrackRef sphereTrack = createTrack( 2.0 * sphereRadius, 2.0 * sphereRadius );

agxVehicle::TrackRef capsuleTrack = createTrack( 2.0 * sphereRadius, 2.0 * sphereRadius );

sphereTrack->setPosition( 0, -1, 0 );

capsuleTrack->setPosition( 0, 1, 0 );

// Initializing the sphere track with several spheres as geometry.

sphereTrack->initialize( [sphereRadius]( const agxVehicle::TrackNode& node )

{

const auto offset = 0.5 * sphereRadius;

const auto numSpheres = std::max( agx::UInt( node.getLength() / offset +

agx::Real( 0.5 ) ),

agx::UInt( 1 ) );

const auto dl = node.getLength() / agx::Real( numSpheres );

agxCollide::GeometryRef geometry = new agxCollide::Geometry();

auto pos = agx::Vec3( 0, 0, 0 );

auto dir = agx::Vec3::Z_AXIS();

for ( agx::UInt i = 0; i < numSpheres; ++i ) {

geometry->add( new agxCollide::Sphere( sphereRadius ),

agx::AffineMatrix4x4::translate( pos ) );

pos += dl * dir;

}

node.getRigidBody()->add( geometry );

} );

// Initializing the capsule track with one capsule per node.

capsuleTrack->initialize( new NodeCapsuleInitializer() );

simulation->add( sphereTrack );

simulation->add( capsuleTrack );

Fig. 22.7 Two tracks initialized with different geometries. Several spheres per node (left) and one capsule per node (right).

Each node doesn’t have to have identical shape/geometry. This example is from tutorial_trackedVehicle.cpp:buildTutorial2 where every fourth node is thicker than the three before:

// Two, different thickness values along the track. Every forth node is thicker than the three before.

const agx::Real defaultThickness = 0.05;

const agx::Real thickerThickness = 0.09;

agxVehicle::TrackRef track = new agxVehicle::Track( 120, 0.4, defaultThickness );

track->add( createTrackWheel( agxVehicle::TrackWheel::Model::SPROCKET, 0.5, 0.3, agx::Vec3( 0, 0, 0 ) ) );

track->add( createTrackWheel( agxVehicle::TrackWheel::Model::ROLLER, 0.6, 0.3, agx::Vec3( 2, 0, 0 ) ) );

track->add( createTrackWheel( agxVehicle::TrackWheel::Model::ROLLER, 0.7, 0.3, agx::Vec3( 4, 0, 0 ) ) );

track->add( createTrackWheel( agxVehicle::TrackWheel::Model::ROLLER, 0.6, 0.3, agx::Vec3( 6, 0, 0 ) ) );

track->add( createTrackWheel( agxVehicle::TrackWheel::Model::IDLER, 0.4, 0.3, agx::Vec3( 8, 0, 0 ) ) );

// Initialization callback when the segmentation of the track has been made.

// When a callback is given to 'initialize' it's up to this callback to assign

// geometries/shapes to the nodes. Note that the track has calculated a length

// of the nodes that has to be taken into account.

agx::UInt counter = 0;

track->initialize( [&]( const agxVehicle::TrackNode& node )

{

agx::Real heightOffset = 0.0;

agx::Real thickness = defaultThickness;

// For every fourth node we add a thicker box.

if ( ( counter++ % 4 ) == 0 ) {

thickness = thickerThickness;

heightOffset = -0.5 * ( thickerThickness - defaultThickness );

}

node.getRigidBody()->add( new agxCollide::Geometry( new agxCollide::Box( 0.5 * thickness,

0.25,

0.5 * node.getLength() ) ),

agx::AffineMatrix4x4::translate( heightOffset, 0, node.getHalfExtents().z() ) );

} );

Fig. 22.8 Track initialized with different shapes/geometries along the track. Every fourth geometry is larger than the three before.

22.1.5.1.4.1. Accessing the nodes in a track

When the track has been initialized it’s possible to iterate the nodes in the track in a few different ways:

for ( agx::UInt i = 0; i < track->getNumNodes(); ++i ) {

agxVehicle::TrackNode* node = track->getNode( i );

...

}

for ( agxVehicle::TrackNode* node : track->nodes() ) {

...

}

Since the track is continuous, i.e., no actual start or end, the use of ranges is more convenient:

// Iterating all nodes.

for ( agxVehicle::TrackNode* node : track->nodes( { 0u, track->getNumNodes() } ) ) {

...

}

// Iterating segments.

const auto numNodesPerSegment = 5u;

for ( agx::UInt nodeIndex = 0; nodeIndex < track->getNumNodes(); nodeIndex += numNodesPerSegment ) {

agxVehicle::Track::NodeRange range{ track->getIterator( nodeIndex ),

track->getIterator( nodeIndex + numNodesPerSegment ) };

for ( agxVehicle::TrackNode* node : range ) {

// Do stuff with the node in range.

}

}

// Since continuous, this is valid to iterate six nodes in a track with 100 nodes.

auto range = agxVehicle::Track::NodeRange{ track->getIterator( 1234u ),

track->getIterator( 1234u + 6u ) };

for ( agxVehicle::TrackNode* node : range ) {

std::cout << node->getIndex() << std::endl;

}

// Prints:

// 34

// 35

// 36

// 37

// 38

// 39

22.1.5.1.4.2. Simulation parameters

Given an initialized track, there are some special handling regarding the interaction between the track and the wheels:

Sprockets: Instead of frictional contacts, nodes will merge with the sprocket - mimicking infinite friction or geared wheel versus track.

Idlers: Default behavior is identical to the sprockets.

Rollers: Frictional contacts. If computational performance is important, make sure the contact material between the rollers and the track nodes has been properly tweaked. E.g, for direct friction models - high surface viscosity.

22.1.5.1.5. Contact materials and friction models

The default friction model and contact material normally isn’t suitable for simulating track versus ground interactions. Mainly because the default friction box is oriented with the world frame and we’re interested in separating the contact parameters along the track (traction) and orthogonal to the track (transverse slip/turning behavior).

For tracked systems, use one of the track friction models:

agxVehicle::TrackBoxFrictionModel

agxVehicle::TrackScaleBoxFrictionModel

agxVehicle::TrackIterativeProjectedConeFrictionModel

These models automatically determine the friction directions from the interacting track bodies/geometries, i.e., they do not require an external reference frame (unlike the legacy oriented friction models). This also means a single friction model instance can be shared across an arbitrary number of tracked vehicles/tracks without per-chassis setup.

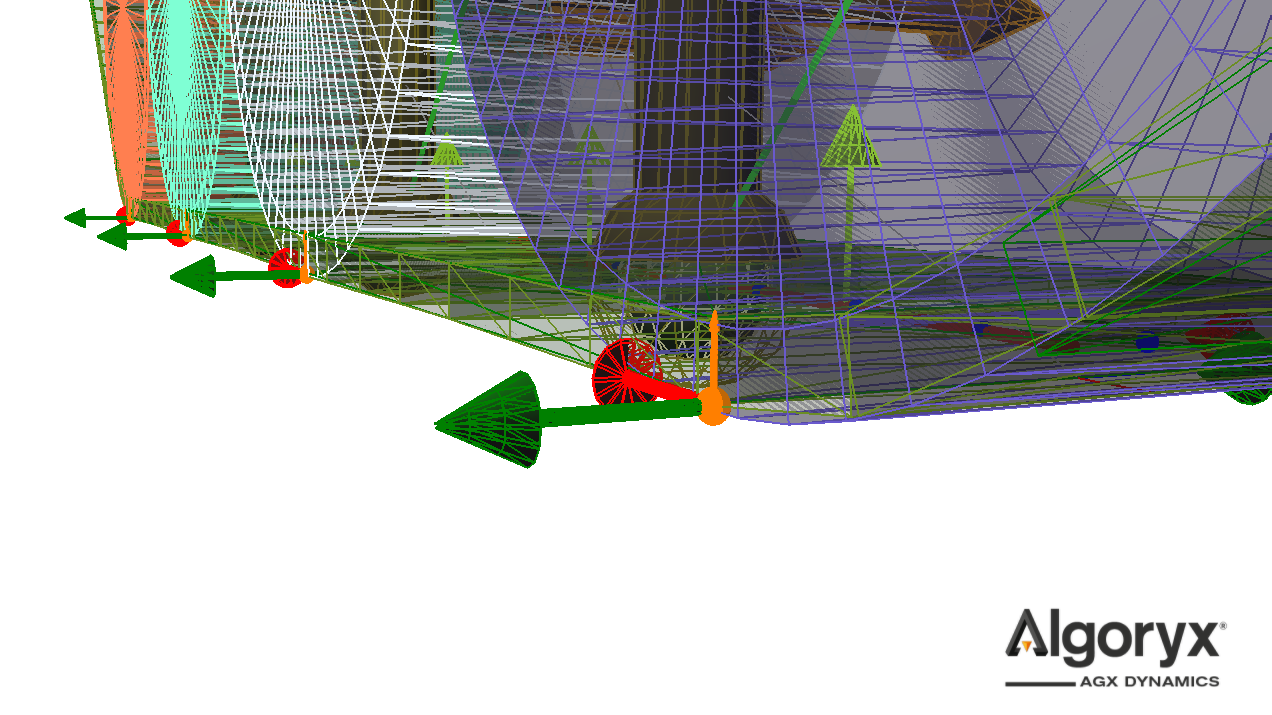

Fig. 22.9 Primary (red) and secondary (green) directions determined by the track friction model. The primary direction is tangent to the track (the track’s positive direction). The track’s positive direction is defined by the rotation axis of the main wheel/sprocket. The sign of the directions is not important for the simulation, what matters is alignment: The primary friction coefficient controls traction along the track, while the secondary friction coefficient controls transverse slip and turning.

Track friction model overview

agxVehicle::TrackBoxFrictionModelBox friction model with track-aligned friction directions. Recommended default for performance/stability when simulating track-ground traction using primary/secondary parameters.

Feature-wise it supports the same key parameters previously used with

agx::ConstantNormalForceOrientedBoxFrictionModel(Section 11.16.3.5):constant normal force magnitude (per-contact friction bound based on a supplied normal force estimate)

optional

scaleWithDepthto scale that bound with contact depth

agxVehicle::TrackScaleBoxFrictionModelScale box friction model with track-aligned friction directions. The nonlinear response of the friction force given the normal force is computationally more expensive but results in accurate friction. See ScaleBoxFrictionModel for further information about this type of friction model.

agxVehicle::TrackIterativeProjectedConeFrictionModelIterative projected cone friction model with track-aligned friction directions. Most accurate, and most computationally expensive, friction model. See IterativeProjectedConeFriction for more details regarding this type of friction model.

General recommendations

Normally a significant amount of nodes are in contact with the ground/floor/other objects, resulting in many contact points. For best numerical and behavioral performance:

Use a direct friction model solve type (

agx::FrictionModel::DIRECToragx::FrictionModel::DIRECT_AND_ITERATIVE) for the track-ground contact material when possible.Prefer

agxVehicle::TrackBoxFrictionModelfor track-ground interactions, optionally with an estimate of the normal force for each contact point. EnablescaleWithDepthif the system is within bounds, performance wise.Set the surface viscosity as high as possible but low enough for the object to not slide with constant speed.

Use different friction coefficients and surface viscosity along and orthogonal to the tracks – usually higher traction (and potentially lower viscosity) along the tracks, and slightly lower transverse traction with higher viscosity orthogonal to the tracks for smooth turning.

Set restitution to zero for better stability and continuous contacts.

Example from tutorial_trackedVehicle.cpp (vehicle shown in Fig. 22.1):

// Setting up materials.

const agx::Real trackDensity = 2000.0;

const agx::Vec2 trackGroundFrictionCoefficients = agx::Vec2( 1000.0, 10 );

const agx::Vec2 trackGroundSurfaceViscosity = agx::Vec2( 1.0E-7, 8.0E-6 );

const agx::Real trackWheelFrictionCoefficient = 1.0;

const agx::Real trackWheelSurfaceViscosity = 1.0E-5;

Note the differences in friction coefficients and viscosity. These has to be chosen to match the performance criterion, stability and behavior. Further:

agx::MaterialRef groundMaterial = new agx::Material( "groundMaterial" );

agx::MaterialRef trackMaterial = new agx::Material( "trackMaterial" );

agx::MaterialRef wheelMaterial = new agx::Material( "wheelMaterial" );

trackMaterial->getBulkMaterial()->setDensity( trackDensity );

ground->setMaterial( groundMaterial );

trackedVehicle->getRightTrack()->setMaterial( trackMaterial );

for ( const auto wheel : trackedVehicle->getRightTrack()->getWheels() )

agxUtil::setBodyMaterial( wheel->getRigidBody(), wheelMaterial );

trackedVehicle->getLeftTrack()->setMaterial( trackMaterial );

for ( const auto wheel : trackedVehicle->getLeftTrack()->getWheels() )

agxUtil::setBodyMaterial( wheel->getRigidBody(), wheelMaterial );

Note that we’re separating ground, wheel and track materials. Normally it’s enough to use the default friction model for the contacts between the track nodes and the wheels, but if the wheels doesn’t respond enough to the friction, a simplified direct track friction model can be used:

#include <agxVehicle/TrackFrictionModels.h>

// Contact material between track nodes and the wheels.

auto trackWheelContactMaterial =

simulation->getMaterialManager()->getOrCreateContactMaterial( trackMaterial, wheelMaterial );

// Slightly simplified friction model between the wheels and the track

// where we estimate the normal force constant @ ten times the mass of

// the chassis. Solved direct.

auto trackFmConstantNormalForce = 10.0 * trackedVehicle->getChassis()->getMassProperties()->getMass();

auto trackWheelFrictionModel =

new agxVehicle::TrackBoxFrictionModel( agx::FrictionModel::DIRECT,

trackFmConstantNormalForce );

trackWheelContactMaterial->setFrictionModel( trackWheelFrictionModel );

// Let the friction coefficient be high and "ease up" the friction constraints

// by using high surface viscosity. Friction properties doesn't affect the

// sprockets or idlers since the nodes will merge to them, simulating infinite

// stick friction against those geared wheel types.

trackWheelContactMaterial->setFrictionCoefficient( trackWheelFrictionCoefficient );

trackWheelContactMaterial->setSurfaceViscosity( trackWheelSurfaceViscosity );

trackWheelContactMaterial->setRestitution( 0.0 );

The contact material between the track nodes and ground is similar but here we include primary and secondary parameters:

// Contact material between track nodes and the ground.

auto trackGroundContactMaterial =

simulation->getMaterialManager()->getOrCreateContactMaterial( trackMaterial, groundMaterial );

// Track-ground friction: use primary (along track) and secondary (transverse) parameters.

// This friction model can optionally scale the maximum friction force with contact depth.

auto trackGroundFrictionModel =

new agxVehicle::TrackBoxFrictionModel( agx::FrictionModel::DIRECT,

trackFmConstantNormalForce,

true /* scaleWithDepth */ );

trackGroundContactMaterial->setFrictionModel( trackGroundFrictionModel );

trackGroundContactMaterial->setFrictionCoefficient( trackGroundFrictionCoefficients.x(),

agx::ContactMaterial::PRIMARY_DIRECTION );

trackGroundContactMaterial->setFrictionCoefficient( trackGroundFrictionCoefficients.y(),

agx::ContactMaterial::SECONDARY_DIRECTION );

trackGroundContactMaterial->setSurfaceViscosity( trackGroundSurfaceViscosity.x(),

agx::ContactMaterial::PRIMARY_DIRECTION );

trackGroundContactMaterial->setSurfaceViscosity( trackGroundSurfaceViscosity.y(),

agx::ContactMaterial::SECONDARY_DIRECTION );

trackGroundContactMaterial->setRestitution( 0.0 );

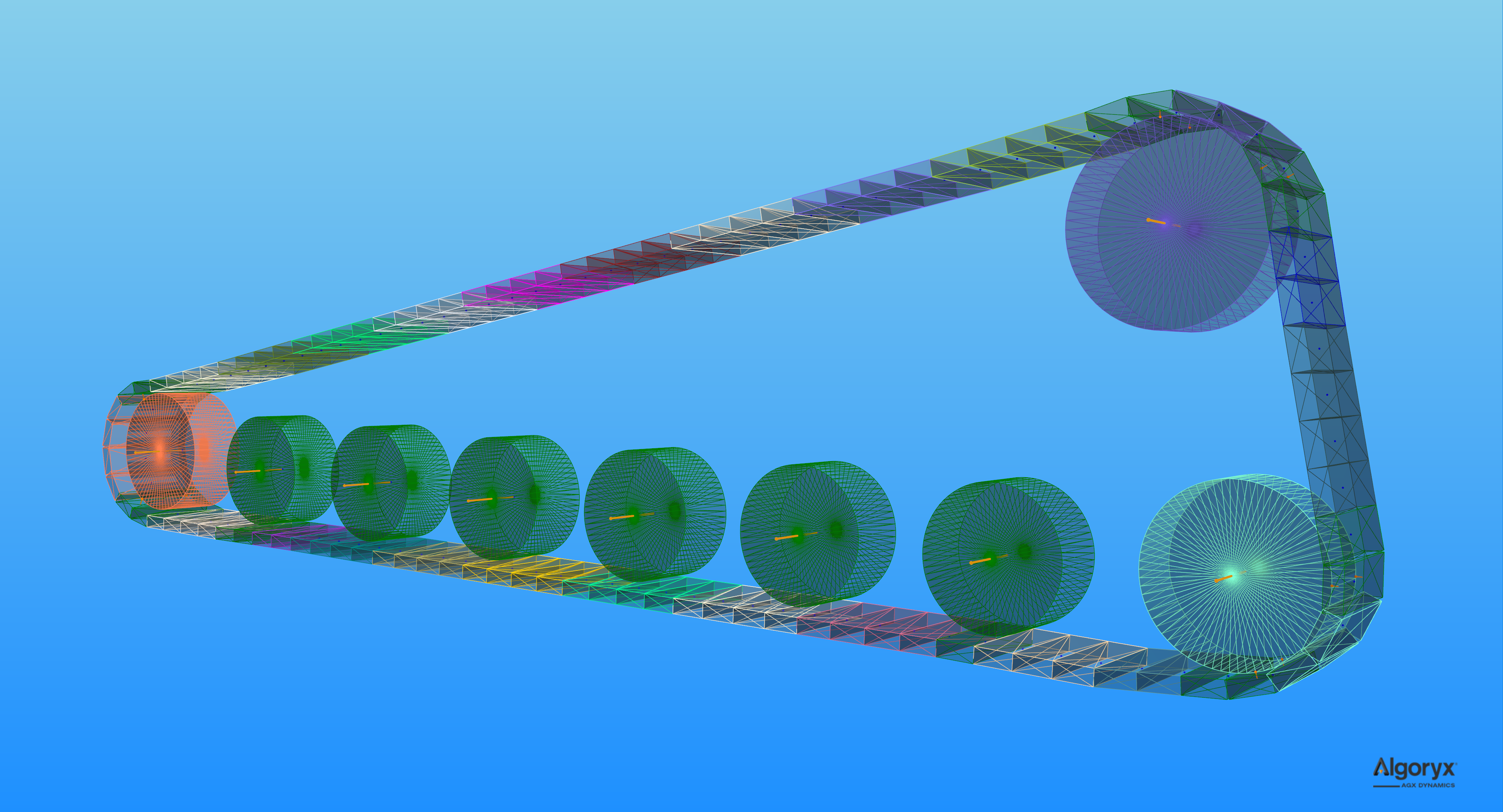

22.1.5.1.6. Merging segments

For performance reasons, it’s possible to enable merging of nodes to segments along the track. The result can be seen in Fig. 22.2 where each segment has a different color. When the nodes are merged together several bodies and constraints aren’t added to the solver (reducing the size of the matrix) and it’s possible to perform contact reduction over the whole segment.

To enable merge (disabled by default):

auto mergeProperties = track->getInternalMergeProperties();

// Default: false

mergeProperties->setEnableMerge( true );

By default (when enabled), three nodes will merge together to a segment. To change the number of nodes to merge simply:

// Setting the number of nodes per segment to 6 (default 3).

mergeProperties->setNumNodesPerMergeSegment( 6u );

Contact reduction is by default minimal which means some contacts will be removed. The other options are none for no contact reduction, moderate for more contacts to be neglected and aggressive for the most intrusive reduction:

// Default: agxVehicle::TrackInternalMergeProperties::MINIMAL (bin resolution 3)

mergeProperties->setContactReduction( agxVehicle::TrackInternalMergeProperties::MODERATE );

The nodes must be aligned to be merged to avoid curvatures to build along the track. The nodes are constrained together with hinges and by default (when merge is enabled) the lock in the hinge is used to force the nodes to their straight/resting position. It’s possible to toggle this feature and set compliance and damping of the lock:

// Default: true

mergeProperties->setEnableLockToReachMergeCondition( true );

// Default: 1.0E-11 (very strong)

mergeProperties->setLockToReachMergeConditionCompliance( 1.0E-6 );

// Default: 3.0 / 60.0

mergeProperties->setLockToReachMergeConditionDamping( 6.0 * timeStep );

// Maximum angle > 0 (in radians) when the nodes may merge.

// Default: 1.0E-5

mergeProperties->setMaxAngleMergeCondition( 6.0E-5 );

22.1.5.1.7. Track properties

All parameters and features implemented in the tracks model are exposed in the agxVehicle::TrackProperties

object. All track instances have an instance of this object, and it is possible for several track instances to share

a single instance of this object, e.g.:

auto globalProperties = track1->getProperties();

track2->setProperties( globalProperties );

track3->setProperties( globalProperties );

agxVehicle::TrackPropertiesRef otherProperties = new agxVehicle::TrackProperties();

track4->setProperties( otherProperties );

track5->setProperties( otherProperties );

It is also possible to load predefined property sets from the Material Library:

if ( properties->loadLibraryProperties( "steel" ) )

std::cout << "Loaded track properties from library!" << std::endl;

You can query available library property sets using:

agx::StringVector available = agxVehicle::TrackProperties::getAvailableLibraryProperties();

There are many parameters in the track properties, some more important than others.

This table, under “Property”, lists the accessor and mutator names – just add get or set and remove any spaces.

E.g., Bending Stiffness is accessed as

properties->setBendingStiffness( stiffness, axis, attenuation ) and

auto k = properties->getBendingStiffness( axis ):

Property |

Description |

Default value |

|---|---|---|

Bending Stiffness |

Resistance to bending deformation per unit length. Typical value is \(E I_a\) where \(E\)

is Young’s modulus and \(I_a\) is the second moment of area. Requires specifying the axis

( |

50 around lateral axis and 1.0e10 around vertical axis |

Tensile Stiffness |

Resistance to stretching/compression in the longitudinal direction per unit length. Higher values give a stiffer track. Default is 1e10 N/m. |

1.0E10 |

Torsional Stiffness |

Resistance to twisting around the track’s longitudinal axis. Typical value \((GJ)/L\). |

1.0e10 |

Shear Stiffness |

Resistance to shearing deformation per unit length, defined as \(GA/L\). Requires specifying

the axis ( |

1.0e10 along both axis |

Bending Attenuation |

Attenuation factor applied in bending stiffness calculations, per axis. |

2.0 |

Shear Attenuation |

Attenuation factor applied in shear stiffness calculations, per axis. |

2.0 |

Tensile Attenuation |

Attenuation factor applied in tensile stiffness calculations. |

2.0 |

Torsional Attenuation |

Attenuation factor applied in torsional stiffness calculations. |

2.0 |

Bending Friction Attenuation |

Attenuation factor used for bending friction calculations. |

2.0 |

Min Stabilizing Hinge Normal Force |

Minimum value of the normal force (the hinge force along the track) used in “internal” friction calculations. I.e., when the track is compressed, this value is used with the friction coefficient as a minimum stabilizing compliance. If this value is negative there will be stabilization when the track is compressed. |

100 |

Stabilizing Hinge Friction Parameter |

Friction parameter of the internal friction in the node hinges. This parameter scales the normal force in the hinge. |

1 |

Enable Hinge Range |

Enable/disable hinge range between track nodes to define how the track may bend. |

true |

Hinge Range Range |

The range (in radians) defining allowed relative angle between track nodes. |

\(-270 \leq \alpha \leq 20\) degrees. |

Enable On Initialize Merge Nodes To Wheels |

When the track has been initialized some nodes are in contact with the wheels. If this flag is true the interacting nodes will be merged to the wheel directly after initialize, if false the nodes will be merged during the first (or later) time step. |

false |

Enable On Initialize Transform Nodes To Wheels |

True to position/transform the track nodes to the surface of the wheels after the track has been initialized. When false, the routing algorithm positions are used. |

true |

Transform Nodes To Wheels Overlap |

When the nodes are transformed to the wheels, this is the final target overlap. |

1.0E-3 |

Nodes To Wheels Merge Threshold |

Threshold when to merge a node to a wheel. Given a reference direction in the track, this value is the projection of the deviation (from the reference direction) of the node direction onto the wheel radial direction vector. I.e., when the projection is negative the node can be considered “wrapped” on the wheel. |

-0.1 |

Nodes To Wheels Split Threshold |

Threshold when to split a node from a wheel. Given a reference direction in the track, this value is the projection of the deviation (from the reference direction) of the node direction onto the wheel radial direction vector. I.e., when the projection is negative the node can be considered “wrapped” on the wheel. |

-0.05 |

Num Nodes Included In Average Direction |

Average direction of non-merged nodes entering or exiting a wheel is used as reference direction to split of a merged node. This is the number of nodes to include into this average direction. |

3 |

Note

The stabilization-related parameters (e.g., Min Stabilizing Hinge Normal Force, Stabilizing Hinge Friction Parameter) and node/wheel merge and hinge range settings are only relevant when using the Full-Degree Tracks Model. These parameters do not apply to the default Low-Degree Tracks Model.

The attenuation constants determines how much to attenuate an oscillation above the Nyquist frequency, default 2. This may be calculated from a (viscous) damping coefficient, see agxUtil::convertDampingCoefficientToSpookDamping and set attenuation to spook damping time / simulation time step.

22.1.5.1.7.1. Internal friction in the hinges

Internal friction in the hinges is used to stabilize the nodes in the track during high tension. The default friction coefficient (Stabilizing Hinge Friction Parameter) is relatively high and could work by default if the track is relatively large (sitting on a large tracked vehicle for example).

When the friction parameter is too low, the tracks will become unstable.

When the friction parameter is too high, the tracks will seem un-bendable, penetrating the wheels and/or the wheels aren’t able to drive the track.

For example the tracked vehicle in tutorial_trackedVehicle.cpp (Fig. 22.1):

track->getProperties()->setStabilizingHingeFrictionParameter( 1.5 );

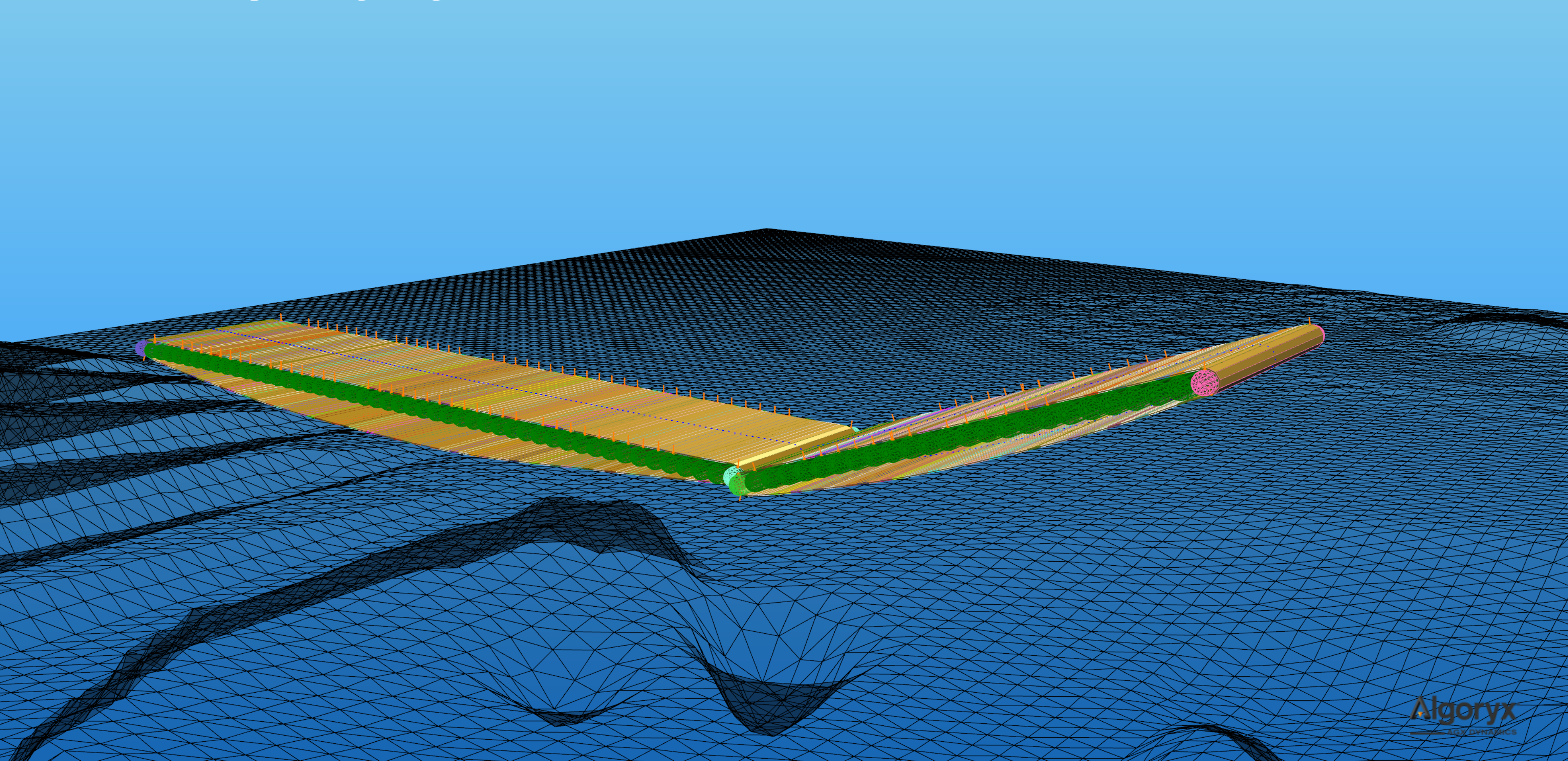

And to simulate a much smaller (thinner where the node mass is significantly smaller) track, in the same tutorial file, simulating a conveyor belt:

conveyor->getProperties()->setStabilizingHingeFrictionParameter( 4.0E-3 );

Fig. 22.10 Simulating conveyor belt using agxVehicle::Track where each roller is a wheel.

22.2. WheelJoint

A WheelJoint is a constraint to attach a wheel to a chassis or the world. The WheelJoint can be created in a few different ways. What they all have in common is that the wheel is the first body and the optional chassis is the second.

When using agx::Frames to construct a WheelJoint, some axes are more important than others. The Y-axis in the first body’s frame specifies the wheel axle. The Z-axis in the second body’s frame is used as suspension axis. When the steering is engaged, the rotation will be around this axis so it can also be referred to as steering axis.

The setup can also be done by using a WheelJointFrame which specifies in world coordinates, the wheel axis, the suspension/steering axis and the intersection point between those two. The two axes that are defined must be perpendicular.

agx::RigidBody* wheel = ... ;

// Position wheel at (1,0,0)

wheel->setPosition( agx::Vec3( 1.0, 0, 0 ) );

// We have the attachment between wheel axle and steering axle at (0.5, 0, 0)

agx::Vec3 worldAttach = agx::Vec3( 0.5, 0, 0 );

// Wheel attachment point and wheel position are on the wheel axle

agx::Vec3 worldWheelAxle = agx::Vec3::Y_AXIS();

agx::Vec3 worldSteeringAxle = agx::Vec3::Z_AXIS();

// Specify a frame

auto wheelJointFrame = WheelJointFrame( worldAttach, worldWheelAxle, worldSteeringAxle );

// Create the constraint. In this case, the wheel is attached to the world

agxVehicle::WheelJoint* wheeljoint = new agxVehicle::WheelJoint( wheelJointFrame, wheel, nullptr );

simulation->add( wheeljoint );

// The suspension is locked by default, release...

auto su_lock = wheeljoint->getLock1D( agxVehicle::WheelJoint::SUSPENSION );

su_lock->setEnable( false );

// .. and enable the range instead to show free movement.

auto su_range = wheeljoint->getRange1D( agxVehicle::WheelJoint::SUSPENSION );

su_range->setEnable( true );

su_range->setRange( -0.1, 0.1 );

// If we don't want rotation around the steering axis, we can lock it

// at its current angle

auto st_lock = wheeljoint->getLock1D( agxVehicle::WheelJoint::STEERING );

st_lock->setPosition( wheeljoint->getAngle( agxVehicle::WheelJoint::STEERING) );

st_lock->setEnable( true );

22.2.1. Connecting to a power-line

A WheelJoint can be powered by a power-line by attaching it to an Actuator. A RotationalActuator cannot be used by itself since a WheelJoint has multiple degrees of freedom, which means that we need to tell the Actuator which of them it should operate on. This is done by passing a WheelJointConstraintGeometry to the RotationalActuator. The WheelJointConstraintGeometry identifies one of the WheelJoint’s free degree of freedom and we chose which one using the same technique as when getting a Lock1D or a Range1D from it.

Continuing the example above.

agxPowerLine::ConstraintGeometryRef wheelAttachAxis =

new agxVehicle::WheelJointConstraintGeometry(wheelJoint, agxVehicle::WheelJoint::WHEEL);

agxPowerLine::RotationalActuatorRef actuator =

new agxPowerLine::RotationalActuator(wheelJoint, wheelAttachAxis);

To control the suspension with a TranslationalActuator we would use agxVehicle::WheelJoint::SUSPENSION instead.

agxPowerLine::ConstraintGeometryRef suspensionAttachAxis =

new agxVehicle::WheelJointConstraintGeometry(wheelJoint, agxVehicle::WheelJoint::SUSPENSION);

agxPowerLine::TranslationalActuatorRef actuator =

new agxPowerLine::TranslationalActuator(wheelJoint, suspensionAttachAxis);

For more information on power-line components and how to connect them see AGX PowerLine.

For a complete example see the tutorial_wheel_joint.agxPy Python tutorial.

22.3. Steering

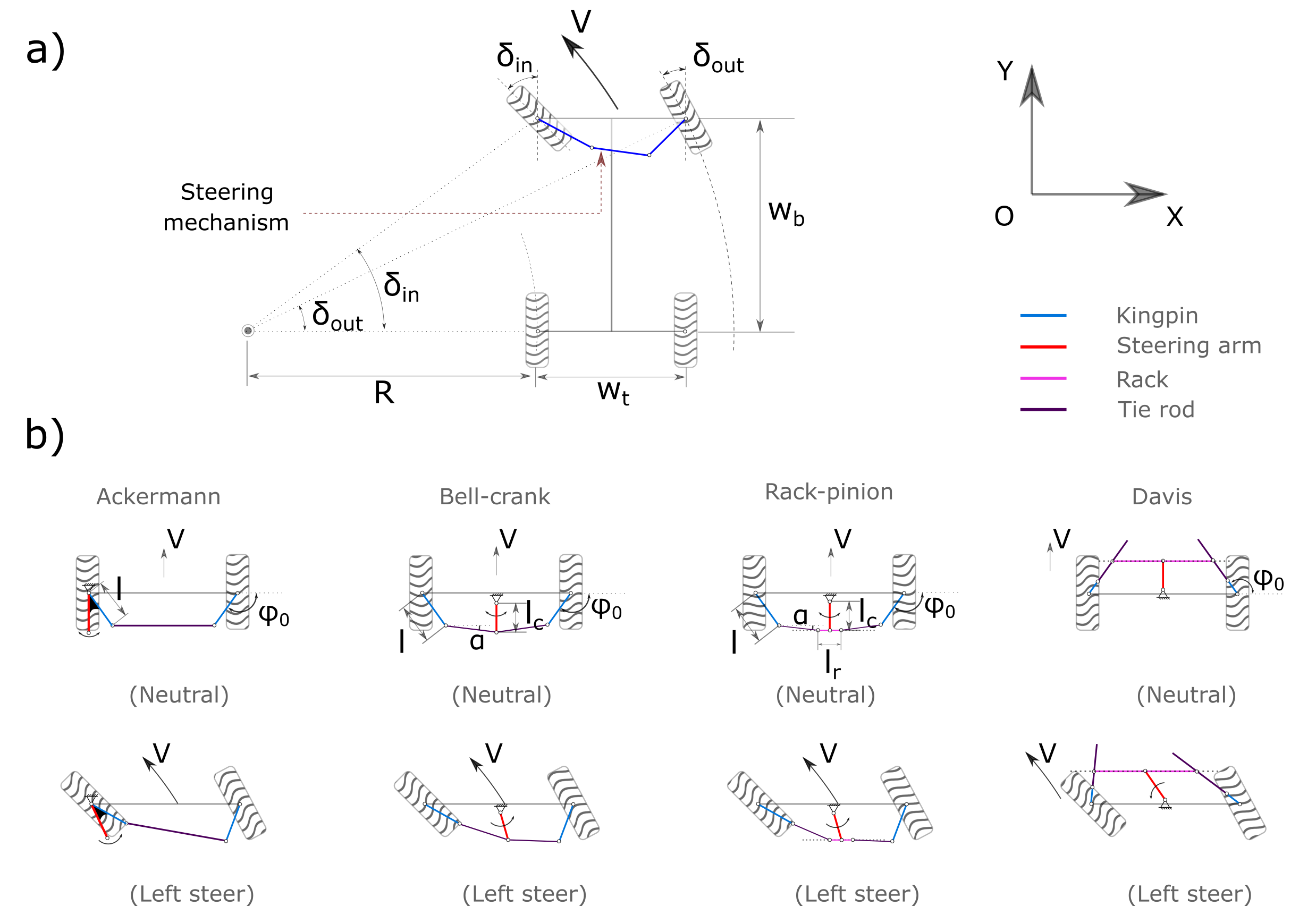

When a car actually turns as shown in Fig. 22.11 a), the steering mechanism is designed to align the wheels simultaneously. The inner wheel will follow a circle with radius \(R\), while the outer wheel follows a concentric circle with radius \(R + W_t\). Note that \(W_t\) refers to the wheel track, \(W_b\) denotes the wheel base.

To minimize the slip and ensure the better turning performance, the front steerable wheels should hold the different steering angles of \(\delta_{\text{in}}\) and \(\delta_{\text{out}}\). According to Ackermann principle, it yields

where \(\delta_{\text{in}}\) refers to the steering angle of the inner wheel, \(\delta_{\text{out}}\) is the ideal steering angle of the outer wheel corresponding to the prescribed \(\delta_{\text{in}}\).

Fig. 22.11 Car steering schematic. a) Turning geometry; b) Four different steering mechanisms.

The generally used Ackermman steering mechanism (See Fig. 22.11 b) is a symmetric planar four-bar linkage. The steering arm, which rigidly connects but not limited to the left kingpin, will transmit the direct steering input of steering wheel to the two front steerable wheels via the trapezoid four-bar linkage. The Ackermann steering geometry is known to be simple and easy for calculation. But it is not always practically possible to implement. Alternatively, there are other steering mechanisms such as bell-crank (also called central-lever [7]), rack-pinion, and davis proposed.

For instance, in a bell-crank steering system, the steering arm rotates, pushing the shared ends of the tie rods to move left or right. This in turn will cause the wheel to turn due to the steering linkages. Bell-crank steering has been reported [7] that is common to wheeled tractors, ATVs, etc.

Regarding the Rack-pinion steering mechanism, the pinion is used to transmit the angular motion of the steering arm into the translational or linear motion of the rack. Rack-pinion steering mechanism is most commonly used to passenger cars [9].

Davis steering mechanism [10] is an exact steering mechanism but is seldom used in practice. It has two sliding pairs in-between the tie rod and the bar. The tie rods are only allowed to move in the direction of the its length. The main disadvantage of the Davis steering is the wear problem of the sliding pairs.

22.3.1. Geometrical parameters

As can be seen from Fig. 22.11 b), all the steering mechanisms share the common parameters of \(\phi_{0}\) and \(gear\). The meaning of these parameters have been described in Table 22.1 as shown below. It can be noticed that the number of independent geometrical parameters varies in terms of the steering mechanisms. For example, there are only one independent parameter of \(\phi_{0}\) needed for Davis steering, and two parameters of \(\phi_{0}\) and \(l\) for Ackermann steering to define the steering geometry. The steering parameters as listed in Table 22.1 are default and optimal. They were selected from [7], [8], [11] and [12].

Parameter |

Unit |

Description |

Ackermann |

BellCrank |

RackPinion |

Davis |

\(\phi_{0}\) |

rad |

Angle between kingpin direction and X axis |

\(\frac{-115}{180}\pi\) |

\(\frac{-108}{180}\pi\) |

\(\frac{-108}{180}\pi\) |

\(\frac{104}{180}\pi\) |

\(l\) |

\(\frac{1}{W_t}\) |

kingpin length |

0.16 |

0.14 |

0.14 |

– |

\(\alpha\) |

rad |

Angle between tie rod and X axis |

– |

0.0 |

0.0 |

– |

\(l_c\) |

\(\frac{1}{W_t}\) |

Steering arm length |

– |

1.0 |

1.0 |

– |

\(l_r\) |

\(\frac{1}{W_t}\) |

Rack or bar length |

– |

– |

0.25 |

– |

gear |

– |

Steering wheel gear ratio |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

side |

– |

Side of steering arm positioned |

0 |

– |

– |

– |

In Table 22.1, "-" indicates that is not applicable.

The users can build their own desired steering geometry using the customized steering geometry parameters. For instance,

auto steerParams = new agxVehicle::SteeringParameters();

// The different values of parameters from the default are prescribed.

steerParams->phi0 = agx::degreesToRadians(-115);

steerParams->l = 0.16;

auto ackermann = new agxVehicle::Ackermann( leftWheel, rightWheel, steerParams);

sim->add( ackermann );

Once the steering mechanism is active, the range of the maximum allowed turning angle according to the geometrical configuration of the steering mechanism will be enabled automatically. This range should not be modified or disabled by the user. However, the user can access the maximum allowed steering angle using the getMaximumSteeringAngle() method.

22.3.2. Building steering

All the steering mechanisms implemented are enforced as three body constraints between each wheel body and the chassis.

The steering mechanisms can be created by simply replacing the “BellCrank” as shown below with the others such as “RackPinion”, “Davis” and “Ackermann”.

SteeringRef steeringMechanism = new agxVehicle::BellCrank( leftFrontWheel, rightFrontWheel );

sim->add( steeringMechanism );

If no SteeringParameters are assigned as an input after the “rightWheel”, the default steering parameters as listed in Table 22.1 will be used.

22.3.3. Steering manipulation

The steering can be manipulated using the setSteeringAngle() method.

class steeringListener : public agxSDK::StepEventListener

{

public:

steeringListener(agxVehicle::Ackerman* ackermann) :

{

}

void pre(const agx::TimeStamp& t)

{

if (t < 1.0) {

ackermann->setSteeringAngle(t);

}

else if (t <= 3.0) {

ackermann->setSteeringAngle(1 - (t-1) / 2);

}

else

{

ackermann->setSteeringAngle(0.0);

}

}

Detailed C++ and python examples with the aforementioned steering mechanisms are

available in tutorials/agxVehicle/tutorial_carSteering.cpp and

python/tutorials/tutorial_carSteering.agxPy.